An alien message in Arrival movie (dredit: Paramount Pictures)

By Susan Schneider

Humans are probably not the greatest intelligences in the universe.

Earth is a relatively young planet and the oldest civilizations could be

billions of years older than us. But even on Earth,

Homo sapiens may not be the most intelligent species for that much longer.

The world Go, chess, and

Jeopardy champions are now all AIs.

AI is projected to outmode many human professions within the next few

decades. And given the rapid pace of its development, AI may soon

advance to artificial general intelligence—intelligence that, like human

intelligence, can combine insights from different topic areas and

display flexibility and common sense. From there it is a short leap to

superintelligent AI, which is smarter than humans in every respect, even

those that now seem firmly in the human domain, such as scientific

reasoning and social skills. Each of us alive today may be one of the

last rungs on the evolutionary ladder that leads from the first living

cell to synthetic intelligence.

What we are only beginning to realize is that these two forms of

superhuman intelligence—alien and artificial—may not be so distinct. The

technological developments we are witnessing today may have all

happened before, elsewhere in the universe. The transition from

biological to synthetic intelligence may be a general pattern,

instantiated over and over, throughout the cosmos. The universe’s

greatest intelligences may be postbiological, having grown out of

civilizations that were once biological. (This is a view I share with

Paul Davies, Steven Dick, Martin Rees, and Seth Shostak, among others.)

To judge from the human experience—the only example we have—the

transition from biological to postbiological may take only a few hundred

years.

I prefer the term “postbiological” to “artificial” because the

contrast between biological and synthetic is not very sharp. Consider a

biological mind that achieves superintelligence through purely

biological enhancements, such as nanotechnologically enhanced neural

minicolumns. This creature would be postbiological, although perhaps

many wouldn’t call it an “AI.” Or consider a computronium that is built

out of purely biological materials, like the Cylon Raider in the

reimagined

Battlestar Galactica TV series.

The key point is that there is no reason to expect humans to be the

highest form of intelligence there is. Our brains evolved for specific

environments and are greatly constrained by chemistry and historical

contingencies. But technology has opened up a vast design space,

offering new materials and modes of operation, as well as new ways to

explore that space at a rate much faster than traditional biological

evolution. And I think we already see reasons why synthetic intelligence

will outperform us.

An extraterrestrial AI could have goals that conflict with those of biological life

Silicon microchips already seem to be a better medium for information

processing than groups of neurons. Neurons reach a peak speed of about

200 hertz, compared to gigahertz for the transistors in current

microprocessors. Although the human brain is still far more intelligent

than a computer, machines have almost unlimited room for improvement. It

may not be long before they can be engineered to match or even exceed

the intelligence of the human brain through reverse-engineering the

brain and improving upon its algorithms, or through some combination of

reverse engineering and judicious algorithms that aren’t based on the

workings of the human brain.

In addition, an AI can be downloaded to multiple locations at once,

is easily backed up and modified, and can survive under conditions that

biological life has trouble with, including interstellar travel. Our

measly brains are limited by cranial volume and metabolism;

superintelligent AI, in stark contrast, could extend its reach across

the Internet and even set up a Galaxy-wide computronium, utilizing all

the matter within our galaxy to maximize computations. There is simply

no contest. Superintelligent AI would be far more durable than us.

Suppose I am right. Suppose that intelligent life out there is

postbiological. What should we make of this? Here, current debates over

AI on Earth are telling. Two of the main points of contention—the

so-called control problem and the nature of subjective experience—affect

our understanding of what other alien civilizations may be like, and

what they may do to us when we finally meet.

Ray Kurzweil takes an optimistic view of the postbiological phase of

evolution, suggesting that humanity will merge with machines, reaching a

magnificent technotopia. But Stephen Hawking, Bill Gates, Elon Musk,

and others have expressed the concern that humans could lose control of

superintelligent AI, as it can rewrite its own programming and outthink

any control measures that we build in. This has been called the “control

problem”—the problem of how we can control an AI that is both

inscrutable and vastly intellectually superior to us.

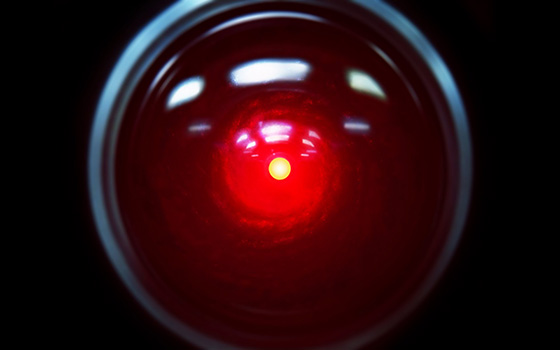

“I’m

sorry, Dave” — HAL in 2001: A Space Odyssey. If you think intelligent

machines are dangerous, imagine what intelligent extraterrestrial

machines could do. (credit: YouTube/Warner Bros.)

Superintelligent AI could be developed during a technological

singularity, an abrupt transition when ever-more-rapid technological

advances—especially an intelligence explosion—slip beyond our ability to

predict or understand. But even if such an intelligence arises in less

dramatic fashion, there may be no way for us to predict or control its

goals. Even if we could decide on what moral principles to build into

our machines, moral programming is difficult to specify in a foolproof

way, and such programming could be rewritten by a superintelligence in

any case. A clever machine could bypass safeguards, such as kill

switches, and could potentially pose an existential threat to biological

life. Millions of dollars are pouring into organizations devoted to AI

safety. Some of the finest minds in computer science are working on this

problem. They will hopefully create safe systems, but many worry that

the control problem is insurmountable.

In light of this, contact with an alien intelligence may be even more

dangerous than we think. Biological aliens might well be hostile, but

an extraterrestrial AI could pose an even greater risk. It may have

goals that conflict with those of biological life, have at its disposal

vastly superior intellectual abilities, and be far more durable than

biological life.

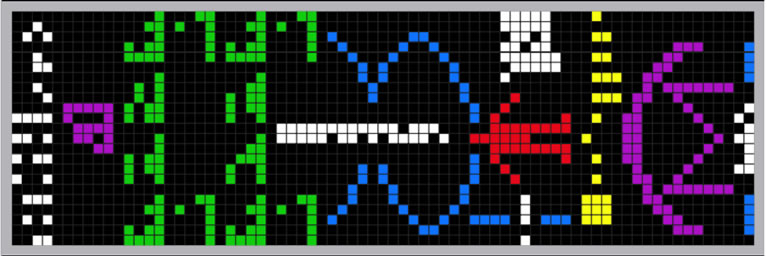

That argues for caution with so-called Active SETI, in which we do

not just passively listen for signals from other civilizations, but

deliberately advertise our presence. In the most famous example, in 1974

Frank Drake and Carl Sagan used the giant dish-telescope in Arecibo,

Puerto Rico, to send a message to a star cluster. Advocates of Active

SETI hold that, instead of just passively listening for signs of

extraterrestrial intelligence, we should be using our most powerful

radio transmitters, such as Arecibo, to send messages in the direction

of the stars that are nearest to Earth.

Why would nonconscious machines have the same value we place on biological intelligence?

Such a program strikes me as reckless when one considers the control

problem. Although a truly advanced civilization would likely have no

interest in us, even one hostile civilization among millions could be

catastrophic. Until we have reached the point at which we can be

confident that superintelligent AI does not pose a threat to us, we

should not call attention to ourselves. Advocates of Active SETI point

out that our radar and radio signals are already detectable, but these

signals are fairly weak and quickly blend with natural galactic noise.

We would be playing with fire if we transmitted stronger signals that

were intended to be heard.

The safest mindset is intellectual humility. Indeed, barring

blaringly obvious scenarios in which alien ships hover over Earth, as in

the recent film

Arrival, I wonder if we could even

recognize the technological markers of a truly advanced

superintelligence. Some scientists project that superintelligent AIs

could feed off black holes or create Dyson Spheres, megastructures that

harnesses the energy of entire stars. But these are just speculations

from the vantage point of our current technology; it’s simply the height

of hubris to claim that we can foresee the computational abilities and

energy needs of a civilization millions or even billions of years ahead

of our own.

Some of the first superintelligent AIs could have cognitive systems

that are roughly modeled after biological brains—the way, for instance,

that deep learning systems are roughly modeled on the brain’s neural

networks. Their computational structure might be comprehensible to us,

at least in rough outlines. They may even retain goals that biological

beings have, such as reproduction and survival.

But superintelligent AIs, being self-improving, could quickly morph

into an unrecognizable form. Perhaps some will opt to retain cognitive

features that are similar to those of the species they were originally

modeled after, placing a design ceiling on their own cognitive

architecture. Who knows? But without a ceiling, an alien

superintelligence could quickly outpace our ability to make sense of its

actions, or even look for it. Perhaps it would even blend in with

natural features of the universe; perhaps it is in dark matter itself,

as Caleb Scharf recently speculated.

The Arecibo message was broadcast into space a single time, for 3 minutes, in November 1974 (credit: SETI Institute)

An advocate of Active SETI will point out that this is precisely why

we should send signals into space—let them find us, and let them design

means of contact they judge to be tangible to an intellectually inferior

species like us. While I agree this is a reason to consider Active

SETI, the possibility of encountering a dangerous superintelligence

outweighs it. For all we know, malicious superintelligences could infect

planetary AI systems with viruses, and wise civilizations build

cloaking devices. We humans may need to reach our own singularity before

embarking upon Active SETI. Our own superintelligent AIs will be able

to inform us of the prospects for galactic AI safety and how we would go

about recognizing signs of superintelligence elsewhere in the universe.

It takes one to know one.

It is natural to wonder whether all this means that humans should

avoid developing sophisticated AI for space exploration; after all,

recall the iconic HAL in

2001: A Space Odyssey. Considering a

future ban on AI in space would be premature, I believe. By the time

humanity is able to investigate the universe with its own AIs, we humans

will likely have reached a tipping point. We will have either already

lost control of AI—in which case space projects initiated by humans will

not even happen—or achieved a firmer grip on AI safety. Time will tell.

Raw intelligence is not the only issue to worry about. Normally, we

expect that if we encountered advanced alien intelligence, we would

likely encounter creatures with very different biologies, but they would

still have minds like ours in an important sense—there would be

something it is like, from the inside, to be them. Consider that every

moment of your waking life, and whenever you are dreaming, it feels like

something to be

you. When you see the warm hues of a sunrise,

or smell the aroma of freshly baked bread, you are having conscious

experience. Likewise, there is also something that it is like to be an

alien—or so we commonly assume. That assumption needs to be questioned

though. Would superintelligent AIs even have conscious experience and,

if they did, could we tell? And how would their inner lives, or lack

thereof, impact us?

The question of whether AIs have an inner life is key to how we value

their existence. Consciousness is the philosophical cornerstone of our

moral systems, being key to our judgment of whether someone or something

is a self or person rather than a mere automaton. And conversely,

whether they are conscious may also be key to how they value

us.

The value an AI places on us may well hinge on whether it has an inner

life; using its own subjective experience as a springboard, it could

recognize in us the capacity for conscious experience. After all, to the

extent we value the lives of other species, we value them because we

feel an affinity of consciousness—thus most of us recoil from killing a

chimp, but not from munching on an apple.

But how can beings with vast intellectual differences and that are

made of different substrates recognize consciousness in each other?

Philosophers on Earth have pondered whether consciousness is limited to

biological phenomena. Superintelligent AI, should it ever wax

philosophical, could similarly pose a “problem of biological

consciousness” about us, asking whether we have the right stuff for

experience.

Who knows what intellectual path a superintelligence would take to

tell whether we are conscious. But for our part, how can we humans tell

whether an AI is conscious? Unfortunately, this will be difficult. Right

now, you can tell you are having experience, as it feels like something

to be

you. You are your own paradigm case of conscious

experience. And you believe that other people and certain nonhuman

animals are likely conscious, for they are neurophysiologically similar

to you. But how are you supposed to tell whether something made of a

different substrate can have experience?

Westworld (credit: HBO)

Consider, for instance, a silicon-based superintelligence. Although

both silicon microchips and neural minicolumns process information, for

all we now know they could differ molecularly in ways that impact

consciousness. After all, we suspect that carbon is chemically more

suitable to complex life than silicon is. If the chemical differences

between silicon and carbon impact something as important as life itself,

we should not rule out the possibility that the chemical differences

also impact other key functions, such as whether silicon gives rise to

consciousness.

The conditions required for consciousness are actively debated by AI

researchers, neuroscientists, and philosophers of mind. Resolving them

might require an empirical approach that is informed by philosophy—a

means of determining, on a case-by-case basis, whether an

information-processing system supports consciousness, and under what

conditions.

Here’s a suggestion, a way we can at least enhance our understanding

of whether silicon supports consciousness. Silicon-based brain chips are

already under development as a treatment for various memory-related

conditions, such as Alzheimer’s and post-traumatic stress disorder. If,

at some point, chips are used in areas of the brain responsible for

conscious functions, such as attention and working memory, we could

begin to understand whether silicon is a substrate for consciousness. We

might find that replacing a brain region with a chip causes a loss of

certain experience, like the episodes that Oliver Sacks wrote about.

Chip engineers could then try a different, non-neural, substrate, but

they may eventually find that the only “chip” that works is one that is

engineered from biological neurons. This procedure would serve as a

means of determining whether artificial systems can be conscious, at

least when they are placed in a larger system that we already believe is

conscious.

Even if silicon can give rise to consciousness, it might do so only

in very specific circumstances; the properties that give rise to

sophisticated information processing (and which AI developers care

about) may not be the same properties that yield consciousness.

Consciousness may require

consciousness engineering—a deliberate engineering effort to put consciousness in machines.

Here’s my worry. Who, on Earth or on distant planets, would aim to

engineer consciousness into AI systems themselves? Indeed, when I think

of existing AI programs on Earth, I can see certain reasons why AI

engineers might actively

avoid creating conscious machines.

Robots are currently being designed to take care of the elderly in

Japan, clean up nuclear reactors, and fight our wars. Naturally, the

question has arisen: Is it ethical to use robots for such tasks if they

turn out to be conscious? How would that differ from breeding humans for

these tasks? If I were an AI director at Google or Facebook, thinking

of future projects, I wouldn’t want the ethical muddle of inadvertently

designing a sentient system. Developing a system that turns out to be

sentient could lead to accusations of robot slavery and other

public-relations nightmares, and it could even lead to a ban on the use

of AI technology in the very areas the AI was designed to be used in. A

natural response to this is to seek architectures and substrates in

which robots are not conscious.

Further, it may be more efficient for a self-improving

superintelligence to eliminate consciousness. Think about how

consciousness works in the human case. Only a small percentage of human

mental processing is accessible to the conscious mind. Consciousness is

correlated with novel learning tasks that require attention and focus. A

superintelligence would possess expert-level knowledge in every domain,

with rapid-fire computations ranging over vast databases that could

include the entire Internet and ultimately encompass an entire galaxy.

What would be novel to it? What would require slow, deliberative focus?

Wouldn’t it have mastered everything already? Like an experienced driver

on a familiar road, it could rely on nonconscious processing. The

simple consideration of efficiency suggests, depressingly, that the most

intelligent systems will not be conscious. On cosmological scales,

consciousness may be a blip, a momentary flowering of experience before

the universe reverts to mindlessness.

If people suspect that AI isn’t conscious, they will likely view the

suggestion that intelligence tends to become postbiological with dismay.

And it heightens our existential worries. Why would nonconscious

machines have the same value we place on biological intelligence, which

is conscious?

Soon, humans will no longer be the measure of intelligence on Earth.

And perhaps already, elsewhere in the cosmos, superintelligent AI, not

biological life, has reached the highest intellectual plateaus. But

perhaps biological life is distinctive in another significant

respect—conscious experience. For all we know, sentient AI will require a

deliberate engineering effort by a benevolent species, seeking to

create machines that feel. Perhaps a benevolent species will see fit to

create their own AI mindchildren. Or perhaps future humans will engage

in some consciousness engineering, and send sentience to the stars.

SUSAN SCHNEIDER is an associate professor of philosophy and

cognitive science at the University of Connecticut and an affiliated

faculty member at the Institute for Advanced Study, the Center of

Theological Inquiry, YHouse, and the Ethics and Technology Group at

Yale’s Interdisciplinary Center of Bioethics. She has written several

books, including Science Fiction and Philosophy: From Time Travel to Superintelligence

. For more information, visit SchneiderWebsite.com.